This article looks at and compares the stars and boxes modeling RDF graph relationships methods.

Graph databases make it easy to create relationships between things. The nodes in the graph represent the things and the edges represent the relationships.

john --employs--> joe

Labeled edges allow us to model different types of relationships between things. However, in practice, relationships are complex entities – simple labeled edges are insufficient – relationships often need their own properties or parameters.

So, for example, if we are modeling an employment relationship between two people, we might want to record, the date at which the relationship started and ended, the job title, the salary, or any other number of details that are considered significant.

john --employs (from: 1/2/2020, salary: 300000)--> joe

In practice, temporal scoping of relationships is a very common requirement to the point of ubiquity – real world relationships are rendered ephemeral by the universe’s relentless temporal march. It is almost as common to have relationships whose weight is effectively determined by some numeric property.

john --shareholder (from: 1/2/2020, holding: 10%)--> IBM

In these and in many similar cases, it is not just the type or label of the relationship that is important, but other properties (date, quantity) are important in the interpretation of the system including the interpretation of whether the relationship is considered to exist (temporal and geographic scoping is interpreted to mean that the existence of the relationship is bounded to a particular time or place).

So how do we model such relationships in graph databases?

In the case of property graphs, the graph relationships are generally simple: edges are JSON documents that can have any number of properties which can be interpreted as qualifiers or scopings by the code that consumes them. Indeed, the simplicity of adding ‘relationship properties’ so is one of the main purported benefits of property graphs compared to RDF graphs, the other main variant.

RDF graph relationships are a little more complicated.

In RDF, the entire structure of the data is a graph, every property, even those with a simple integer value, is represented as just another edge in the graph – we cannot speak of properties without using relationships as each property is itself an edge of the graph. The edges are, by definition, uniquely defined by their labels and there is no facility for adding properties to them. The triple – two nodes and an edge – is the atomic unit.

There are 2 principle solutions to this apparent conundrum of modeling RDF graph relationships, which we might call ‘boxes’ and ‘stars’

Stars – RDF*

The extension to RDF known as RDF* is explicitly an effort to overcome the lack of relationship properties in RDF by changing the syntax and semantics of the underlying language.

In RDF, traditionally, the subject of a triple is the IRI representing the thing that the triple is a property of. RDF* extends this by allowing triples themselves to by the subjects of other triples. So, we can write:

joe> --from--> 1/2/2020

joe> --salary--> 30000

These star properties are considered to be properties of the specific john --employs-->joe edge, providing scoping, qualifiers and other types of relationship properties on top of the basic RDF labeled edges.

Boxes – Reified Relationships

The second approach is quite different and builds on top of RDF rather than changing it.

In this approach, we model the relationship itself as a thing with its own properties including properties that link the relationship thing to the things being related.

This approach is formally known as reification but informally known as boxing – we create an object as a box around the relationship properties and add the qualifier properties to the box.

For example, we might create an object to represent an employment relationship as follows:

employment --type--> Employment Relationship

employment --employer--> john

employment --employee--> joe

employment --from--> 1/2/2020

In this approach, there is no fundamental difference between a thing representing a relationship and any other type of thing except that these reified relationships have, by definition, properties that point at other things. Otherwise, they’re just another type of thing in the graph.

The only important thing we need for this approach is that we really need a way of defining object types or classes of data objects with strongly typed properties to define what types of things can be related through the different types of graph relationships.

If we want to use algorithms that treat such objects as relationships in traversals, we need to ensure regularity of representation and semantic validity or else we will need to include error checking code in all subsequent traversals.

With strongly typed properties and object type hierarchies we can trivially write generic traversal code and implement whatever rich algorithms on top without worrying about the low-level RDF representation.

Comparing and contrasting the two approaches

The downside of the box approach is that it introduces a layer of indirection into the graph. Rather than being able to see the employs relationship directly between joe and john, we have to construct it from 2 properties passing through the reified relationship object:

john --employs--> joe

becomes:

john <-- employer -- employment -- employee --> joe

However, such indirection is unavoidable given the fact that employs is no longer actually a simple relationship – it has properties and its endpoints are just some of those properties – the lack of indirection in the -- employs --> relationship is illusory.

So, from this point of view, the indirection is not really a downside, it is an unavoidable consequence of wanting to use relationships with properties other than their endpoints. Or, to put it more strongly, from a purely data-modeling perspective, the boxing approach is the correct solution.

The problems with the RDF* graph relationships approach are many and profound.

Firstly, from a conceptual point of view, it misunderstands the basic concept of an RDF graph – triples are the lowest level unit for structuring data in RDF, the basic idea is to assemble structure and create representations of complex real-world entities from patterns of triples and this works perfectly well for modeling complex relationships.

The human-level graph of things and their relationships emerges from the use of consistent patterns of groups of triples and should not be confused. The whole point of RDF is that it allows you to create arbitrary structures of interlinked entities to represent whatever complex real-world entity you want, not that the internal structure is a direct expression of a specific high-level conceptualization of the world.

Secondly, from a language structure point of view, it fundamentally shatters the simplicity and regularity of the RDF triple form – its strongest point – and complicates each and every subsequent action. Henceforth, you must distinguish between subjects that represent triples and those that represent ordinary entities and change your process accordingly.

Thirdly, from a logical soundness point of view, it introduces nth-order expressivity into the language (e.g. << from 1/2/2020> status: inactive>) and all the well-known problems of impredicativity that come with that, not to mention the impact on the computational complexity of traversing the graph for inference and reasoning – one of the benefits of RDF is that a large amount of research effort has been devoted to understanding the computational complexity of different classes of reasoning axioms. As soon as you introduce meta-triples, we’re back into an unknown world of unbounded complexity.

Fourthly, and finally, in practice, it avoids the problem – when we want to add things like temporal scoping, security classifications, weightings, and such properties to graph relationships, we generally want the scoping and properties to apply to the object as an object rather than a set of structurally unrelated triples – the whole point of data management technologies is that they should help provide useful abstractions to which we can apply such properties, not that it should kick the problem back to the user.

If I have to write:

< from 1/2/2020>

< salary 30000>

then I have to maintain the coordination of both statements for the future and for any future changes – if the high-level relationship changes, I have to map this to a collection of low-level triples and the system provides no help.

Using a boxed class to represent a relationship avoids all of these problems completely and is semantically correct and consistent.

So why have people bothered with RDF* and all of the complexities that come with it?

In some ways, it stems from theoretical confusion over the nature of RDF graphs and a misguided desire to apply the much simpler model of adding properties to edges from property graphs.

But more importantly, it stems from a failure of the RDF research world to provide a good and simple way of defining strongly typed objects with strongly typed properties – class definitions that ensure data conforms to the required shape.

To define a useful relationship type, we need to be able to specify certain things:

- the types of the endpoints of the relationship (e.g. employs is a relationship between a Person and a Person)

- cardinalities of the relationship edges (e.g. the Employment Relationship has exactly one employer and one employee)

To build a graph that we can easily query and traverse from these components, imposing such constraints on the data is particularly important because it allows us to build reliable patterns which abstract away the underlying triples, and we don’t have to deal with situations where we find an employee relationship without an employee, or which links to an Address object rather than a Person object.

In TerminusDB this is achieved by using standard OWL classes and properties to describe the data-objects and applying a closed world reasoning regime to its interpretation. Other approaches involve complex combinations of RDFS, OWL, and SHACL to achieve similar goals, but are far less sound and simple than just extending OWL to support a close world regime, as we have done in TerminusDB.

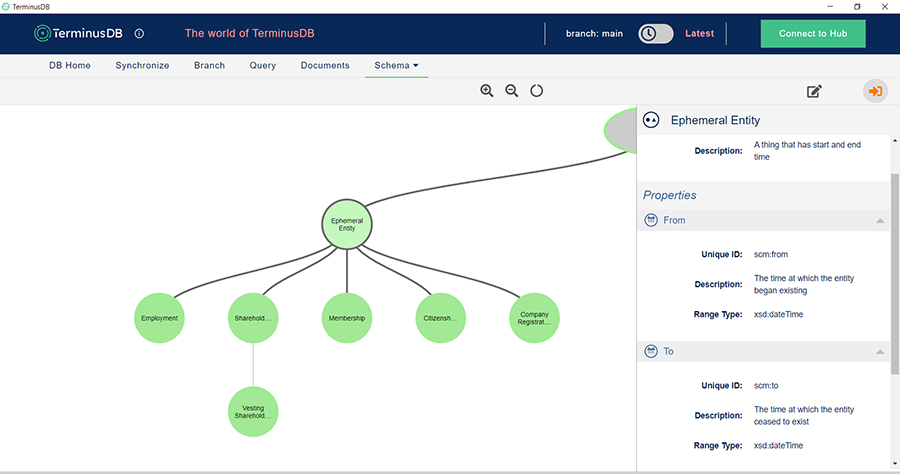

This gives us not only the ability to describe complex relationship types and have strong guarantees as to the shape of the data, but it also provides a sound framework for multiple inheritances, which allows us to very efficiently apply general-purpose regular scopings across many different object types.

So for example, we can define a “Temporally Scoped” object type and give it start and end properties. Then we make any of our temporally scoped entities or relationships subclasses of this class – suddenly everything has the same temporal scoping properties and can be uniformly processed by temporally aware processes.