This is part 1 of our 4 part warts-and-all introduction to graph technologies and this first part focuses on RDF Database. We’ll also be looking at Property Graphs, Graph Schemas, Linked Data, and concluding with an article called Why Graph Will Win. It should give you a solid introduction to the world of graph and associated challenges, while also offering a firm view that graph is the correct way to approach these complex problems. Enjoy!

Graph databases are on the rise, but amid all the hype it can be hard to understand the differences under the hood. This is the first article in a four-part series describing the fundamental technologies that graph databases use under the hood. Unlike most articles that you will come across, this is neither marketing nor is it a tutorial — it’s a warts and all description of their strengths and weaknesses — stuff I have learned over 20 years of pain and suffering, in the hope that I can help somebody else out to avoid having to learn these lessons the hard way.

There are two major variants of graph databases in the wild — RDF graphs (aka triple-stores) and Labelled Property Graphs. In this, the first article in the series, I’ll describe RDF Database (Resource Description Framework Database), its strengths and weaknesses, and where it came from. In subsequent articles, I’ll describe labeled property graphs and some of the standards and technologies that have been built on top of them.

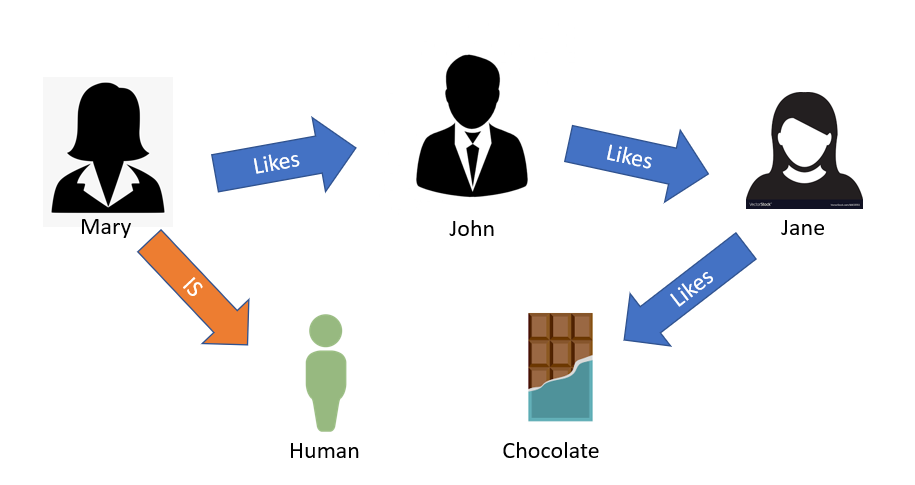

subject -> predicate -> object

mary -> likes -> john

mary -> is -> human

john -> likes -> jane

jane -> likes -> chocolate

When joined together a set of triples forms an RDF Database: a graph consisting of nodes and edges — it really is as simple as that.

Triples can be combined to represent a knowledge graph which computers can interpret and reason about. When joined together, they form a natural graph, where the predicates (the middle part of the triple) are interpreted as edges and the subjects and objects are the nodes.

So far so good. In fact, triples are the ideal atom of information — 3 degrees of freedom in our basic atomic expressions is sufficient for a self-describing system, 3 has the highest information density of any integer. We can build up a set of triples that describes anything describable. Binary relations, on the other hand, which are the basis of tables and traditional databases, can never be self-describing: they will always need some logic external to the system to interpret them — 2 degrees of freedom is insufficient.

The triple as logical assertion is also a tremendously good idea — one consequence is that we don’t have to care about duplicate triples — if we tell the computer that Mary likes John a million times, it is the same as telling it once — a true fact is no more nor less true if we say it 1000 times or 1 time.

But RDF defined a lot more than just the basic idea of subject-predicate-object logical assertion triples. It also defined a naming convention where both the subject and predicate of each triple had to be expressed as a URL. The object of each triple could either be expressed as a URL or as a literal such as a number “6” or string “hat”. So our triples need to be of the form:

http://my.url/john -> http://my.url/likes -> http://my.url/jane

The basic idea being that if we load the URL of any subject, predicate or object, we will find the definition of the node or edge in question at that URL. So, if we load http://my.url/likes into our browser, we find the definition of the likes predicate. This design decision has both costs and benefits.

The cost is immediate — URLs are much longer than the variable names used in programming language and they are hard to remember. This slows down programming as we can’t just use simple strings as usual, we have to refer to thing by their full URL. RDF tried to mitigate this cost by introducing the idea of namespace prefixes. That is to say, we can define: prefix ex = http://my.url/ and then we can refer to john as ex:john rather than the full URL http://my.url/john.

From a programming point of view, these namespace prefixes certainly make it much easier to use an RDF Database, but there is still considerable cost over traditional simple variable names — we have to remember which prefixes are available, which entities and predicates belong to which namespace, and type several extra characters for every variable.

Programming is an art form in which productivity is dependent on reducing the number of things that we have to remember at each step, because we are concentrating on a big picture problem and need to focus all our concentration there rather than on the details of the lines of code. Speed of typing is also of paramount importance because we are almost always in a hurry and the faster we go, the less chance there is that we will forget something important along the way. From that point of view, using URLs as variable names, even with prefixes, is a massive cost to programming speed.

The benefits, on the other hand, are seen in the medium and long term. There is an old computer science joke:

there are only 2 hard things in computer science: naming things, cache coherence and off-by-one errors.

This is a good joke because it is true — naming things and cache coherence really are the hardest things to get right — while off-by-one errors are just extremely common errors that novices make in loop control.

RDF databases help significantly to address both of the hard problems — by forcing coders to think about how they name things and by using an identifier that is uniformly and universally addressable, the problem of namespace clashes (people using the same name to talk about different things) is greatly reduced. What’s more, linking an entity to its definition, also greatly helps the cache coherence problem — everything has an authoritative address at which the latest definition is available.

From an overall systems perspective, the extra programmer pain is tremendously worth it — if we know how something is named, we can always look it up and see what it is. By contrast, when we are dealing with traditional databases, the names used have no meaning outside the context of the local database — tables, rows, and columns all have simple variable names which mean nothing except within the particular database in which they live, and there is no way of looking up the meaning of these tables and columns because it is opaque — embedded in external program code.

So, up to this point, it’s all positive — the use of logical subject-predicate-object triples as URL -> URL -> URL is actually a very good starting point for building data structures. They allow us to describe anything we want in a way that is universally and uniformly named, addressable, retrievable, and self-describing. The extra pain in having to use URLs instead of simple variable names is, in the long run, very much worth it.

RDF, however, is much more than just the basic triple form. It also defines a set of reusable predicates. The most important one of these is rdf:type — which allows us to define our entities as having a particular type:

ex:mary -> rdf:type -> ex:human

This triple defines john as being of type ‘human’. This provides us with the basis for constructing a formal logic in which we can reason about the properties of things based on their types — if we know john is a human and not, for example, a rock, we can probably infer things about him without knowing them directly.

Formal logics are very powerful indeed because they can be interpreted by computers to provide us with a number of useful services — logical consistency, constraint checking, theorem proving, and so on. And they help tremendously in the battle against complexity — the computer can tell us when we are wrong.

The Problem With RDF

Unfortunately, however, that is where the good stuff ends. Almost every other design decision that went into the RDF specification was disastrously wrong.

The first point is rather minor — RDF Databases support ‘blank nodes’, that is to say, nodes that are not identified by a URL but instead by a local identifier (given a pseudo prefix like “_:name”). This is supposed to represent the situation where we want to say “some entity whose name I do not know” — to capture for example assertions such as “there is a man in the car”. As we don’t know the identity of the man, we use a blank node rather than a URL to represent him.

This was simply a mistake — it confuses the identity of the real-world thing with the identity of the data structure that represents it. It introduces an element into the data structure that is not universally addressable and thus cannot be linked to outside its definition for no good reason. Just because we don’t know the identity of the thing, does not and should not mean we cannot address the structure describing the unknown thing.

What’s worse, RDF tools generally interpret blank nodes in such a way that their identifiers can be changed at will, meaning that it is hard to mitigate the problem in practice. Still, tool stupidity notwithstanding, such a poor design choice can be mitigated at the cost of some effort — for example by using a convention whereby blank nodes within a document can be addressed as a sub-path of the URL of the document that contains them. This at least allows them to be accessed through the same mechanism as all other nodes are.

The second major design flaw relates to the semantics that were published to govern the interpretation of triples and their types. To cut a long and technical story short, what they defined was — in a technical sense — nonsense. Logic, in a formal sense, is like probability: seemingly simple to the uninitiated but in fact horrendously difficult and full of counter-intuitive results and many traps for the naïve.

It is very easy to construct a logical system that is incoherent or inconsistent — where the rules tell us that a given fact is both true and false. The most famous example is known as Russell’s paradox — the set of all sets that do not contain themselves — a paradoxical definition since this set must both contain itself and not contain itself. The basic rule of logic is that if it is legal to express such paradoxes, then the logic is inconsistent — we can’t rely on assertions defined in the logic.

RDF included explicit support for making statements about statements — what they called higher order statements — without putting in place any rules that prevented the construction of inconsistent knowledge bases. To put it simply, these semantics were completely wrong (or impredicative). In fact, RDF also included a broad suite of containers, distributive predicates, and various other elements — in each case they were similarly wrong.

In 1999, RDF 1.0 was made a standard by the web’s governing body, the W3C, and was enthusiastically promoted as the core of the future semantic web, despite the fact that it effectively described a nonsense system. How did this happen?

“ The web is the domain of engineers, not logicians. With the rise of the commercial software industry in the 1970s and 1980s, computer science based on formal logic was largely abandoned. Instead we got software engineering, based on turning programmers into money in as short a space of time as possible.”

To tell the truth, this wasn’t surprising — the web is the domain of engineers, not logicians. With the rise of the commercial software industry in the 1980s, computer science based on formal logic was largely abandoned. Instead, we got software engineering, based on turning programmers into money in as short a space of time as possible.

Almost nobody in the IT industry understands anything about formal computational logic nowadays save a few eccentric researchers laboring away in their labs on obscure topics completely ignored by industry. As a result, when it comes to things such as schema languages, constraint logics, and so on, the industry’s most distinguished bodies repeatedly publish international standards that are just nonsense.

In any case, the logical inconsistency of the RDF standard was only a minor factor in its failure to gain widespread adoption. A much worse mistake concerned the serialization format that was chosen to express RDF textually: RDF/XML. Back in 1999, XML was relatively new and fashionable, so it was a natural choice, but the way in which RDF had to be shoehorned into XML created a horrifically confusing and ugly monster. In modern RDF circles, a format known as turtle is used to serialize triples as text. It is reasonably simple to interpret and concise to construct:

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#>.

@prefix ex: <http://my.url/>.

ex:mary a ex:human;

ex:likes ex:john.

In RDF/XML this is constructed as follows:

<rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:ex="http://my.url/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about=”ex:mary”>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="ex:human"/>

<ex:likes rdf:resource=”ex:john”/>

</rdf:Desciption>

</rdf:RDF>

Back in 1999 when the RDF and RDF/XML standards were published, the social web was just taking off and a simple technology called RSS (really simple syndication) was at its core. RSS 0.91 was a very simple and popular meta-data format which allowed bloggers to easily share their updates with third party sites, enabling people to see when their favourite site had published updates, so that they didn’t have to check manually.

Probably the greatest mistake ever made by the W3C was imposing RDF/XML as the new standard for RSS — RSS 1.0. There was a very quick revolution of bloggers who found the new standard vastly increased the complexity of sharing updates, without giving anything extra in return. Bloggers generally stuck to the old non-RDF 0.91 version — the ideological wars that this created effectively turned the world of web-developers against RDF — a blow that RDF and the W3C have never really recovered from.

Conclusion: There Is Hope for RDF Database

Despite the terrible mistakes made in the definition of the RDF specification, at its very core, RDF remains by far and away from the most advanced and sophisticated mechanism available for describing things in a computer interpretable way. And the standard did not remain static — the W3C issued a series of new standards that refined and extended the original RDF and built several other standards on top of it.

The second part of this series on graph fundamentals covers Labelled Property Graphs, the second major variant of graph databases today, while the third part covers graph schema languages with particular focus on OWL, the most ambitious attempt yet to provide us with a language for talking about data.