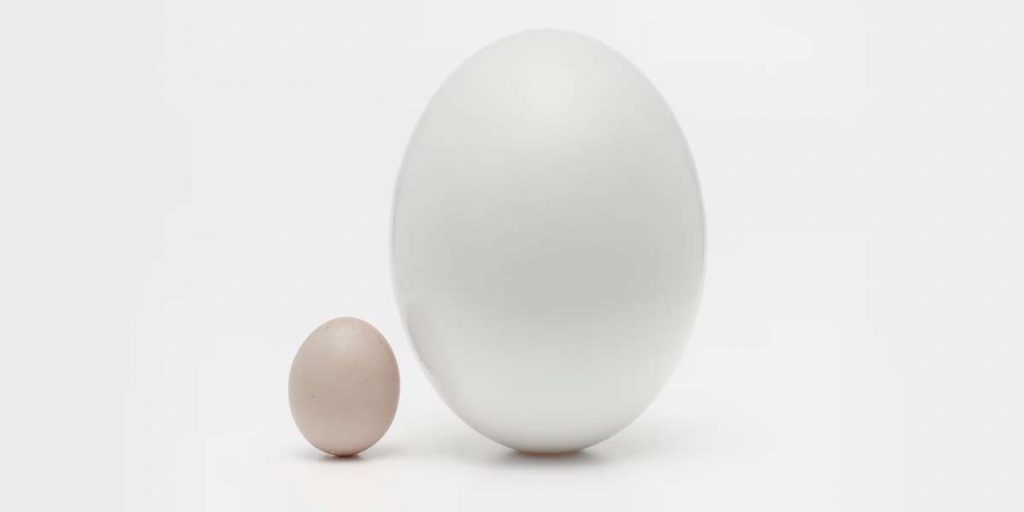

In the design of distributed data collaboration, it turns out that size matters a lot. And smaller is better.

Despite the enduring popularity of the traditional RDBMS (with SQL as its query language) there have been many innovations in database design over the last decades which hope to solve specific questions that make traditional designs inconvenient or unworkable. These include everything from time-series databases to distributed key-value stores.

When we were designing TerminusDB we were concerned with one very specific problem: collaboration.

As we were working on the Seshat global history database we needed a database that could enable researchers all over the world to collaborate on data collection on a large dataset with a very complex schema.

Git has created a very compelling model for collaboration in software using distributed revision control. This works essentially by storing objects which represent changes between versions. These change-objects can then be communicated, used to produce merges (which are also change-objects), and then decisions can be made to resolve potential conflicts (with another change object). The model has proved fantastically helpful in the development of software and is now almost completely dominant in software engineering practice.

Small is the new big

While we share many of the same problems in data that we have in code, there is a big difference: Data tends to be big.

Even large codebases find it hard to compete with relatively modest database tables. CSVs with millions of lines are not uncommon, though millions of lines of code are quite rare.

Real attention has to be paid to how the change-objects are represented. However, we also have to worry about what we can fit into memory. If our data has to go back and forth to disk, we can be in real trouble with performance. This is particularly relevant for graphs, which tend to have complicated interconnections.

The implications of size on the usability of collaboration in data have driven many of the design decisions we have taken in TerminusDB.

Currently, our backend storage system (TerminusDB-Store) uses succinct data structures to represent our graphs. Succinct data structures are *self-indexing* data structures that approach the information-theoretic minimum size of representation.

Self-indexing structures represent the data in the index itself. This has the advantage that you don’t have to keep a separate index along with the data, helping to reduce size overhead.

Right now our identifiers are stored using a front-coded dictionary. This seems to work well for identifiers that are based on URIs which tend to share large prefixes and result in decent compression while retaining reasonable lookup performance.

In order to store our edge connections, we use adjacency lists and wavelet trees which help us to reconstruct a path through the graph rapidly in most typical querying patterns.

When we actually send layers around we compress them using gzip (which we found to give us a reasonable size/time trade-off in practice). And are thus able to get the sizes even more manageable.

Getting Smaller all the time

We’ve gone a long way in making our data terse so it can easily be shared and enable a whole new horizon of possibilities in data sharing and data integration. The healthy data ecosystem of the future that we hope to help bring about will absolutely require that we can move changes around effectively.

However, we are nowhere near done hitting rock bottom in terms of size. The current layout for datatypes is much less efficient than it could be and we already have a detailed plan in our roadmap for reducing this further while also getting a sizeable performance increase for typical queries.

We are excited about the features we plan to roll out in our roadmap, but for the end-user, the ones that they will probably notice most in facilitating collaboration will be the ones that shrink the data.