When it comes to languages for rule processing, prolog has them all beat. It has so many exciting features that make it incredibly flexible, among them:

- backtracking: we can try several strategies to solve a problem, and roll back if one doesn’t work. This also give us generators and testors using the same framework, enabling guess and check approaches to algorithms.

- homoiconicity: which enables incredible metalogical madness including term and goal expansion and simplifying the writing of meta-interpreters.

- DCGs (Declarative Clause Grammars): regexps are great, but when your language isn’t regular, DCGs give us one of the nicest ways to parse input around.

Yet when trying to write large software packages in anger for industrial purposes, there are some unfortunate warts that tend to plague this otherwise beautiful language. I’ve compiled a fairly long mental list, but right now I want to talk about two of these awkward elements and what to do about them.

When you write a predicate in prolog, you can often make a very efficient choice between clauses in the predicate by carefully choosing terms that enable us to discriminate between the clauses we would like to “fire”.

p(term_a) :- write(term_a).

p(term_b) :- write(term_b).

When we invoke p(term_a) we are graciously treated to the expected printout. And perhaps even better we, with a prolog such as swipl, we don’t even end up with any remaining choice-points due to the indexing of the argument, making our choice efficient as well.

However, in large-scale projects, it can happen that we call p/1 with something quite unexpected, perhaps with term_c, due either to a typo, or a thought-o. Prolog’s method of dealing with this is to silently fail — and since failure in prolog is a normal course of events, the result can lead to irritating bug searches which take quite a while to narrow the problem to its source.

Of course, what we want for p/1 is to correctly type it. That is, we want to be able to add some additional information to p about the domain of its arguments such that we can dynamically, or even better, statically, determine that they are not of the required variety.

Hindley Milner and type_check

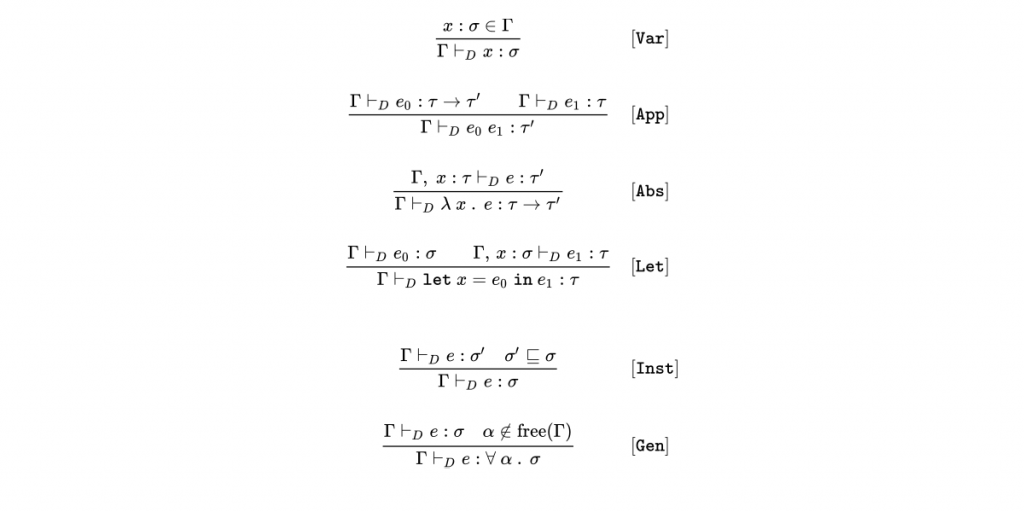

Enter Hindley-Milner (HM), a type system that allows us to write down just the sort of thing we’re concerned about when we call p/1. HM has a great number of advantages, allowing both inference of types in many cases, and the ability to write down our types in a nice algebraic fashion. It also includes many extensions which might be convenient in the case of prolog.

So how does HM work? Thanks to the work of Tom Schrijvers et al. we can try it out with the swipl package ‘type-check’. For our p above we can now write the following:

:- use_module(library(type_check)).

:- type term ---> term_a ; term_b.

:- pred p(term).

p(term_a) :- write(term_a).

p(term_b) :- write(term_b).

Here we add a type ‘term’ which is term_a, or (represented by the ‘;’) a term_b. We can now declare the arguments of our predicate p with a ‘pred’ declaration.

Now when we load our file, ‘type_check’ will attempt to find any type errors present in the code.

The first result of loading this file is the following message:

% TYPE WARNING: call to unknown predicate `write(term_a)'

% Possible Fixes: - add type annotation `::' to call

% - replace with call to other predicate

... :-

'HERE'(write(term_a)).

% TYPE WARNING: call to unknown predicate `write(term_b)'

% Possible Fixes: - add type annotation `::' to call

% - replace with call to other predicate

... :-

'HERE'(write(term_b)).

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

% Type checking for module `first_blog' done:

% found type errors in 0 out of 2 clauses.

% Well-typed code can't go wrong!

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

Essentially our type-checker is telling us that it doesn’t know anything about write/1. Unfortunately, the majority of standard ISO prolog is unknown to type-check. To really make it work properly for building software in the large we would need to add type annotations to our library. However, we have three different workarounds provided by ‘type-check’.

The first two work-arounds I’ll demonstrate in tandem.

:- pred p(term).

p(term_a) :- write(term_a) :: write(any).

p(term_b) :- write(term_b) :< write(any).

Here we add type annotations to the code to inform the type checker that it can assume the type of the arguments of write/1 to be of type ‘any’. Both of these annotations appear to achieve the same outcome, however the former adds an additional wrapper to the call, ensuring that the arguments are actually of the appropriate type dynamically. The second is nothing more than a “trust-me” style hint to the type checker.

Similarly, we can build up a database of trust-me style hints using the following syntax:

:- trust_pred write(any).

We can imagine how this could be extended to much of the standard library, for instance:

:- trust_pred append(list(T),list(T),list(T)).

This establishes that any call with append is to be treated as though it takes a list of some unknown type, another list of that same unknown type, and returns an output list of that type.

Given we have used one of these methods to properly type our predicate p, we can look at what type_check reports when we utilize p wrongly.

:- use_module(library(type_check)).

:- type term ---> term_a ; term_b.

:- pred p(term).

p(term_a) :- write(term_a) :: write(any).

p(term_b) :- write(term_b) :: write(any).

:- pred q.

q :- p(term_c).

The predicate q/0 is where we have inserted our buggy call. And indeed, type_check reports:

TYPE ERROR: expected type `unknown_type' for term `term_c'

inferred type `term' in goal: p(term_c) in clause: q :- 'HERE'(p(term_c)).

Well, type_check has shown us our error, and we can now correct our bug at compile time rather than having to wait until we see the error in production.

Typing in the real world

This is really great, but there are some caveats. The type_check library really needs to have a few kinks ironed out for it to work in industrial practice.

The first thing is that the full standard library needs to be given appropriate typing in a library so that you don’t have to constantly run around typing everything. And in order to do this, type_check needs to be made module aware, which it currently is not. Module-awareness adds a good deal of complexity as well — how do we import types for instance?

Second, the addition of dynamic checks at boundaries is absolutely fantastic, and precisely the right way to ease a language like prolog into using static typing disciplines. However, when should we apply these type checks? This leads us to the question of mode checking. We will look at dynamic type checking and dynamic mode checking in the next article on mavis.