The (nearly) final part of our 4 part warts-and-all introduction to graph technologies focuses on Linked Data. It covers RDF, Property Graphs, Graph Schemas, Linked Data, and concludes with an article called Why Graph Will Win. It should give you a solid introduction to the world of graph and associated challenges, while also offering a firm view that graph is the correct way to approach these complex problems. Enjoy!

By the mid-2000s, it was clear that the vision of the semantic web, as set out by Tim Berners Lee in 2001, despite a huge amount of initial hype and investment, remained largely unrealized.

The basic idea that a network of machine-readable, semantically rich documents would form a ‘semantic web’, much like the world wide web of documents, was proving much more difficult than had been anticipated. This prompted the emergence of the concept of ‘linked data’, again promoted by Tim Berners Lee, and laid out in two documents published in 2006 and 2009.

Linked data was, in essence, an attempt to reduce the idea of the semantic web down to a small number of simple principles, which were meant to capture the core of the semantic web without being overly prescriptive over the details.

Linked Data Principles

The 4 basic principles to publish linked data were:

- Use URIs for things

- Use HTTP URIs

- Make these HTTP URIs dereferenceable, returning useful information about the thing referred to

- Include links to other URIs to allow the discovery of more things.

We can supplement these 4 principles with a fifth, which was originally defined as a ‘best practice’ but which effectively became a core principle:

- “People should use terms from well-known RDF vocabularies such as FOAF, SIOC, SKOS, DOAP, vCard, Dublin Core to make it easier for client applications to process Linked Data”

These 5 points effectively defined linked data movement and remain at the heart of current semantic web research.

1 and 4 are encapsulated within RDF (linked data was not defined to mean only RDF but, in practice, RDF is almost always used by people publishing linked data), are were restating the basic design ideas of the semantic web with a less prescriptive approach.

The second principle just recognized that, in practice, people only ever really used HTTP URLs – and by 2006, HTTP had become the dominant mechanism for communicating with remote servers, as it remains today – so this was very sensible.

So far so good. The 3rd principle was also restating a concept that had been implicit in RDF and the semantic web – the idea that if you submit an HTTP GET to any of the URLs used in linked data, you should get useful information about the thing that is being referred to. So, for example, if you have a triple:

prefix ex <http://my.url/>

ex:jane ex:likes ex:chocalate

And you open http://my.url/jane in your browser, the server should return some useful information about jane, while if you open http://my.url/likes, you should get useful information about the ‘likes’ concept.

This principle means that linked data can be ‘self-documenting’ – because each concept used has documentation that can be found at the given URL, giving us a simple and well-known mechanism for knowing where to find the documentation of stuff.

However, the big problem is that this principle is too weak – it does not dictate what the useful information is, what it should contain or what services it should support. It should really contain a machine-readable definition of the term, not just unspecified useful information. Without that stipulation, we can’t really automate much — we don’t know what type of information will be found at any given URL, or even what format it will be in. A human has to look at it to interpret it.

Then when we come to the fifth and final principle — the reuse of popular vocabulary terms – things really get messy.

The motivation for this principle is clear, everybody was creating their own ontologies with their own classes and properties, reinventing the wheel again and again rather than reusing existing ontologies. Surely, it would be better if people reused the same terms rather than reinventing their own.

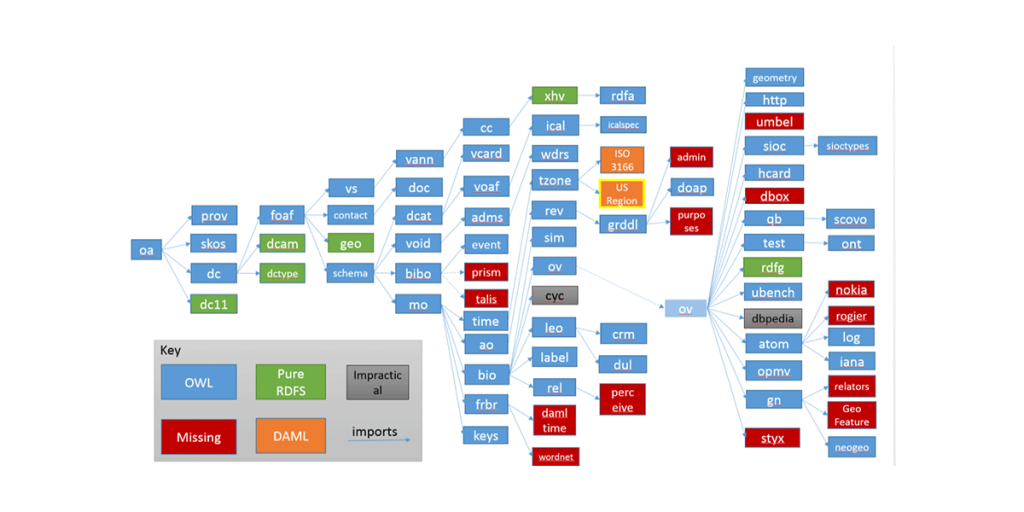

However, the big problem is that the well-known ontologies and vocabularies such as foaf and dublin-core that have been reused, cannot really be used as libraries in such a manner. They lack precise and correct definitions and they are full of errors and mutual inconsistencies [1] and they themselves use terms from other ontologies – creating huge and unwieldy dependency trees.

If, for example, we want to use the foaf ontology as a library, we need to also include several dozen dependant libraries, some of which no longer exist. So, the linked data approach, in fact, just uses these terms as untyped tags — there is not a clear and usable definition of what any of these terms actually mean — people just bung in whatever they want – creating a situation where there is no reliable semantics to any of these terms.

Linked Open Data Cloud

The Linked Open Data Cloud is the great achievement of the linked data movement – it shows a vast array of interconnected datasets, incorporating many of the most important and well-known resources on the internet such as Wikipedia.

Unfortunately, however, on closer examination, it is far less impressive and useful than it might appear – due to the lack of well-defined common semantics across these datasets, the links are little more than links – they cannot be automatically interpreted by computers.

What’s worse, where semantic terms are used, they are very often used erroneously. For example, it is commonplace to use the term owl:sameAs to create links between instances in different datasets that are about the same real-world thing, and likewise, it is common to use the term owl:equivalentClass to refer to classes that refer to the same real-world thing. In these cases, while the terms are well-defined, their defined meanings are quite different from how they are actually used – they assert that the classes or instances are logically the same thing and can be unified.

If we follow the correct interpretation, the consequence is that everything blows up because they are almost never in fact logically equivalent.

This is not to say that such links are useless – it is manifestly useful to a human engaged in a data-integration task to know which data-structures are about the same real-world thing – but that falls far short of the vision of the semantic web – it is supposed to be a web of knowledge for machines, not humans.

The fundamentally decentralized conception of linked data carries further challenges. It takes resources to create, curate, and maintain high-quality datasets and if we don’t continue to feed a dataset with resources, entropy quickly takes over.

If we want to build an application that relies upon a third party linked dataset, we are relying upon whoever publishes that dataset to continue to feed it with resources — this is a risky bet in general and particularly risky when we are dealing with academic research in which almost all resources are focused on novelty and almost none on infrastructure and maintenance.

For example, the Wordnet linked dataset has been extensively used in commercial applications, but the dataset maintainers at the University of Southampton have long since run out of resources to maintain it [2].

The semantic web — as illustrated in the diagram above – is predictably littered with abandoned ontologies and datasets. Simply continuing to build linked datasets without considering the resourcing problem is building on the foundations of sand.

Linked Data Summary

In summary, the linked data movement as it exists suffers from several critical problems which continue to prevent adoption outside of academic research.

Firstly, the specifications are too weak to enable automatic processing by machines in any meaningful way.

Secondly, it creates dependencies on third parties without any sustainable economic model. Even in a perfect world without free-riders, there are many situations in which a third party might be getting much more value from a dataset than the dataset maintainer who bears the cost.

If we actually want to make linked data and the semantic web work the first thing that we need to do is to radically reduce the ambition of the movement.

Firstly, we should only create links between datasets that have well-defined, sound, and mutually compatible machine-readable semantics.

Secondly, we should resource the maintenance of high-quality datasets as a public service, rather than leave them subject to the novelty-loving whims of academic research.

[1] Linked Data Schema: Fixing unsound foundations. K. Feeney, G. Mendel Gleason, R. Brennan, Semantic Web, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 53-75, 2018

[2] https://lod-cloud.net/dataset/rkb-explorer-wordnet

That was the final article of our warts-and-all 4 part Graph Fundamentals series. Recap on the others by following the link below:

- Part 1: RDF DB

- Part 2: Labeled Property Graphs

- Part 3: Graph Schema Languages

The series refrains putting any spin on graph technology to paint the truth about the pros and cons of each subject. However, to supplement this series and to underpin our belief in graph, read the last article: Why Graph Databases Will Win.

Thanks for reading!